The Importance and Role of APIs That Make Streaming Media Possible

As content providers strive to make the streaming viewer experience more personalized and friction-free, the role of API-enabled microservices is growing rapidly. But, just like the complex interactions that occur under the hood of your car, many probably don’t think much about the APIs that make feature-rich services possible. After all, they just work, until they don’t. And it doesn’t take much to frustrate subscribers who can switch to another provider with the click of their remote or a command to Alexa or Siri. Without APIs, streaming media services would not exist. There are three broad phases of a typical streaming media experience where APIs are essential:

- Phase 1 – Login and selection: When the viewer opens the app, their saved credentials are checked against a subscriber database and they are automatically authenticated. Information stored in their user profile is then fetched, allowing the app to present a personalized carousel of content based on the subscriber’s viewing history and preferences, including new releases and series the viewer is watching or has watched recently. This involves a recommendation engine responsible for delivering the thumbnail images of recommended content for the subscriber. APIs must accomplish all of this in seconds.

- Phase 2 – Initiating playback: Once the subscriber has selected their content and pressed “play,” a manifest request is generated, providing a playlist for accessing the content. This may involve interactions with licensing databases and/or advertising platforms for freemium content, all handled by APIs.

- Phase 3 – Viewing experience: During playback, APIs manage multiple aspects of the experience, including serving up ads. In some cases, these ads may be personalized for the subscriber, requiring a profile lookup. If the subscriber decides to switch platforms midstream—say from their big-screen TV to their tablet—APIs come into play to make that transition seamless, so the content picks up right where it paused on the other platform.

API calls are occurring throughout playback, tracking streaming QoS to optimize performance given the subscriber’s bandwidth, network traffic and other conditions. Additional information, such as whether the subscriber watched the entire movie or bailed out partway through, may be delivered back to their profile to further refine their preferences (Most content providers only count a program “watched” once the subscriber has reached some percentage of completion). That’s just a high-level view—in practice, there may be hundreds or thousands of API interactions, each of which must occur in milliseconds to make this complex chain of events happen seamlessly. If just one of these interactions breaks down, the user experience can quickly go from streaming to screaming.

With APIs being so critical to the user experience there are many potential points of failure. The wrong profile may be loaded. The recommendation engine may not serve up the suggested content thumbnails. The manifest request could fail, triggering the dreaded “spinning wheel of death,” preventing content from loading. Ads may hang up, disrupting or even blocking playback completely. Some of these API failures are merely annoying—but others are in the critical path, preventing content delivery.

In addition to APIs essential for playback functions—manifest calls, beaconing for QoS, personalization, etc.—other APIs play crucial roles for business intelligence. APIs that gather data on user engagement, such as percentage of completion of content, are important for analytics that inform critical decisions impacting content development budgets and advertiser negotiations. This data is also used for subscriber interactions outside the platform, such as email touches to encourage subscribers to continue watching a series or alert them to new content matching their preferences. Continually keeping a finger on the pulse of subscriber behavior is crucial for business decisions that create a sticky service that builds subscriber loyalty. APIs make it possible.

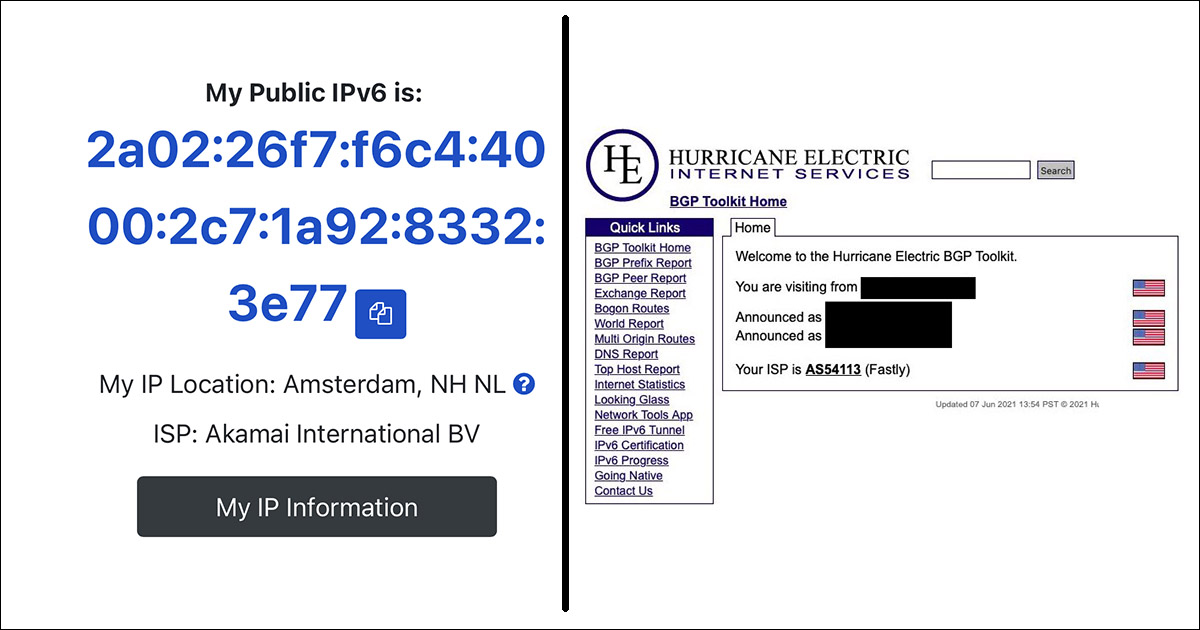

Given the role APIs play, ensuring their performance, reliability and security should be a priority for streaming media providers. The first step is recognizing their importance and understanding which APIs are in the critical path. These may need a higher degree of protection, such as having backups for them. Delivering critical APIs from the edge, from endpoints closer to the subscriber, can also help maximize both their reliability and their performance. Another good practice is keeping your APIs on separate hostnames from your content (api.domain vs. domain/api), allowing each to be tuned for optimum performance and reliability. Making sure your content delivery network has robust security features is also important, as APIs are an increasingly common vector for cyberattacks, which is why you are seeing more CDN vendors offering API protection services.

With consumers demanding a continuous supply of new streaming features and capabilities, APIs will only become more numerous and more critical to business success. So it only makes sense to pay as close attention to how your APIs are architected and delivered as you do to your content.

Since AT&T closed its purchase of Time Warner, Viacom merged with CBS, Disney acquired Fox’s studio and key cable networks, Discovery took over Scripps Networks and Amazon looking to acquire MGM, content consolidation has been the main focus in the industry. With so many OTT services for consumers to pick from, alongside multiple monetization models (AVOD, SVOD, Free, Hybrid), fragmentation in the market will only continue to grow. We all know that content is king and is the most important element in a streaming media service. But with so many OTT services all having such a good section of content, the next phase of the OTT industry will be all about the differentiation of quality and experience amongst the services and the direct impact this has on churn and retention.

Since AT&T closed its purchase of Time Warner, Viacom merged with CBS, Disney acquired Fox’s studio and key cable networks, Discovery took over Scripps Networks and Amazon looking to acquire MGM, content consolidation has been the main focus in the industry. With so many OTT services for consumers to pick from, alongside multiple monetization models (AVOD, SVOD, Free, Hybrid), fragmentation in the market will only continue to grow. We all know that content is king and is the most important element in a streaming media service. But with so many OTT services all having such a good section of content, the next phase of the OTT industry will be all about the differentiation of quality and experience amongst the services and the direct impact this has on churn and retention.