Rebuttal to FCC Commissioner: OTT, Cloud and Gaming Services Should Not Pay for Broadband Buildout

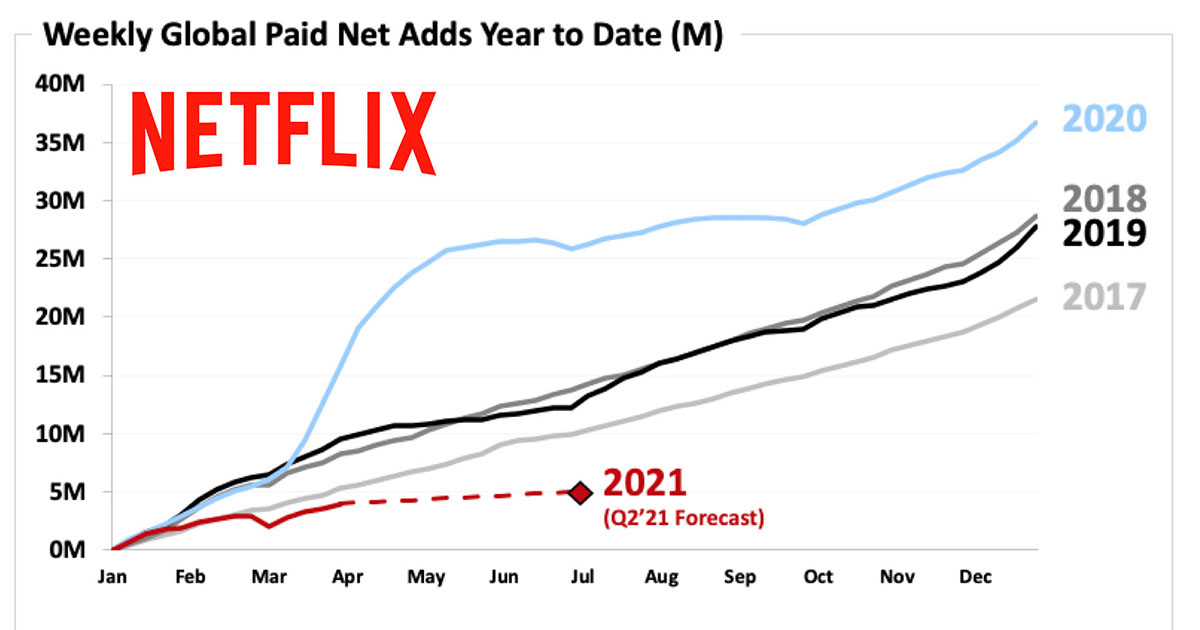

Brendan Carr, commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), published an op-ed post on Newsweek entitled “Ending Big Tech’s Free Ride.” In it, he suggests that companies such as Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Microsoft, Google and others, should pay a tax for the build-out of broadband networks to reach every American. In his post he blames streaming OTT services as well as gaming services like Xbox and cloud services like AWS for the volume of traffic on the Internet. There are a lot of factual problems with his post from both a business and technical standpoint, which is always one of the main problems when regulators get involved in topics like this. They don’t focus on the facts of the case but rather their “opinions” disguised as facts. The Commissioner references a third-party post-doctoral paper as his argument, which contains many factual errors when it comes to numbers disclosed by public companies, some of which I highlight below.

The federal government currently collects roughly $9 billion a year through a tax on traditional telephone services—both wireless and wireline. That pot of money, known as the Universal Service Fund, is used to support internet builds in rural areas. The Commissioner suggests that consumers should not have to pay that tax on their phone bill for the buildout of broadband and that the tax should be paid by large tech companies instead. He says that tech companies have been getting a “free ride” and have “avoided” paying their fair share.” He writes that “Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google generated nearly $1 trillion in revenues in 2020 alone,” saying it “would take just 0.009 percent of those revenues,” to pay for the tax. The Commissioner is ignoring the fact that in 2020, Apple made 60% of their revenue overseas and that much of it comes from hardware, not online services. Apple’s “services” revenue, as the company defines it, made up 19% of their total 2020 revenue. So that $1 trillion number is much, much lower, if you’re counting revenue from actual online services that use broadband to deliver the content.

If the Commissioner wants to tax a company that makes hardware, why isn’t Ford Motor Company on the list? They make physical products but also have a “mobility” division that relies on broadband infrastructure for their range of smart city services. Without that broadband infrastructure Ford would not be able to sell mobility services to cities or generate any revenue for their mobility division. You could extend this notion to all kinds of companies that make revenue from physical goods or commerce companies like eBay, Etsy, Target and others. Yet the Commissioner specifically calls out video streaming as the problem and references a paper written in March of this year as his evidence. The problem is that the paper is full of so many factually wrong numbers, definitions and can’t even get the pricing of streaming services accurate, something the Commissioner clearly hasn’t noticed.

The paper says YouTube is “on track to earn more than $6 billion in advertising revenue for 2020”. No, YouTube generated $19.7 billion revenue in 2020. The paper also says that Hulu’s live service costs $4.99 a month, when in actuality it costs $65 a month. It also says that the on-demand version of Hulu costs $11.99 a month when it costs $5.99 a month. There are many instances of wrong numbers like this in the report that can’t be debated and are simply wrong. Full stop. The authors say the goal of the paper is to look at the “challenge of four rural broadband providers operating fiber to the home networks to recover the middle mile network costs of streaming video entertainment.” They say that “subscribers pay about $25 per month subscriber to video streaming services to Netflix, YouTube, Amazon Prime, Disney+, and Microsoft.” That’s not accurate. YouTube is free. If they mean YouTube TV, that costs $65 a month. The paper also uses words like “presumed” and “assumptions” when making their arguments, which isn’t based on any facts.

The paper also points out that the data and methodology used in the report to come to their conclusions “has limitations” since traffic is measured “differently” amongst broadband providers. So only a slice of the overall data is being used in the report and the methodology collection isn’t consistent amongst all the providers. We’re only seeing a small window into the data being used in the repot, yet the Commissioner is referencing this paper as his “evidence”. The paper also references industry terms from as far back as 2012 saying they have “adapted” them to today, which is always a red flag for accuracy.

The paper also incorrectly states that “The video streaming entertainment providers do not contribute to middle or last mile network costs. The caching services provided by Netflix and YouTube are exclusionary to the proprietary services of these platforms and entail additional costs for rural broadband providers to participate.” Netflix and others have been putting caches inside ISP networks for FREE, which saves the ISP money on transit. Apple will also work with ISPs via their Apple Edge Cache program. For anyone to suggest that big tech companies don’t spend money to build out infrastructure for the consumers benefit is simply false. Some ISPs choose not to work with content companies offering physical or virtual caches but that’s based on a business decision they have made on their own. In addition, when a consumer signs up for a connection to the Internet from an ISP, the ISP is in the business of adding capacity to support whatever content the consumer wants to stream. That is the ISPs business and there is no valid argument that an ISP should not have to spend money to support the user.

The paper stats that, “Rural broadband providers generally operate at close to breakeven with little to no profit margin. This contrasts with the double-digit profit margins of the Big Streamers.” Disney’s direct-to-consumer streaming division which includes Disney+, Hulu, ESPN+ and Hotstar lost $466 million in Q1 of this year. What “double-digit profit margins” is the paper referencing? Again, they don’t know the numbers. The paper also gets wrong many of their explanations of what a CDN is, how it works, and how companies like Netflix connect their network to an ISP like Comcast. The paper also shows the logo of Hulu and Disney+ on a chart listing them under the Internet “backbone” category, when of course the parent owner of those services, The Walt Disney Company, doesn’t own or operate a backbone of any kind. The paper argues that since rural ISPs have no scale, they can’t launch “streaming services of their own” like AT&T has. Of course, this is 100% false and there are many third-party companies in the market that have packaged together content ready to go that any ISP can re-sell as a bundle to their subscribers, no matter how many subscribers they have.

According to a 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the FCC’s number one challenge in targeting and identifying unserved areas for broadband deployment was the accuracy of the FCC’s own broadband deployment data. Congress recently provided the FCC with $98 million to fund more precise and granular maps. You read that right, the FCC was given $98 million dollars to create maps. In March of 2020, Acting FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel said these maps could be produced in “a few months,” but that estimate has now been changed to 2022. Some Senators have taken notice of the delay and have demanded answers from the FCC.

It’s easy to suggest that someone else should pay a tax without offering any details on who exactly it would apply to, how much it would be, what the classifications are to be included or omitted, which services would or would not fall under the rule, how much would need to be collected and over what period of time. But this is exactly what Commissioner Carr has done by calling out companies, by name, that he thinks should pay a tax. All while providing no details or proposal and referencing a paper filled with factual errors. I have contacted the Commissioner’s office and offered him an opportunity to come to the next Streaming Summit at NAB Show, October 11-12, and debate this topic with me in-person. If accepted, I will only focus on the facts, not opinions.

This morning it was

This morning it was