Cloud Based Multiscreen Workflows To Become A Billion Dollar Market Over Time

As NAB kicks off, we’re seeing a number of exciting deployments of cloud-based digital media solutions. From a trend of conceptual trials and early announcements last year, this indicates a remarkable, and remarkably fast, maturing of the industry. Cloud is solving real pain points for the M&E industry which is still struggling to come to terms with the volume, fragmentation and technological complexity that ubiquitous video gives rise to.

From a research perspective, Frost & Sullivan has released a new study called “Global Media and Entertainment Solutions on the Cloud”. We’ve taken an in depth look at five verticals where the cloud is most impacting M&E applications today – transcoding, media asset management, animation, B2B productivity workflows, and niche services such as captioning and metadata insertion. A brief summary of its findings are available here.

One source of confusion we’ve seen in the market is that cloud is still used as a nebulous term for three distinct use cases – deployments within a private data center (so-called virtualized execution), deployments in a public data center (in other words using Infrastructure as a Service or IaaS) and pay-as-you-go service licenses (in other words Software as a Service or SaaS). The two former use cases are influencing product designs away from dedicated hardware and appliance form factors towards software form factors that are more amenable to virtualization.

The growth in SaaS is more fundamentally transforming the industry by lowering barrier to entry for smaller or less technology-savvy media companies, lowing barrier to entry for any size of media company looking to establish new, experimental or short-term services, and by dramatically reducing total cost of ownership of a wide range of online video services while also providing scalability, flexibility and agility. However, for solutions to optimally deliver on the promise of the cloud, it is critical that they be architected from the ground up for the cloud. On-premise products that are ported naively to the cloud cannot deliver reliability if for example virtual machines need to be rebooted or a network connection goes down. Such products will also be less able to intelligently spin distributed computing resources up and down in response to fluctuating workloads.

While the total revenues accrued under the SaaS model for media and entertainment applications are in the neighborhood of $100 million in 2013, we expect this to rise explosively quickly, approaching the billion dollar mark by 2020, driven not only by a compelling value proposition but also by rapidly maturing solutions and improved market awareness. To more closely gauge how media and entertainment companies are harnessing the cloud today and anticipating using it in the future, we also embarked on a consumer-facing research initiative. Specifically, we spoke with senior executives in marquee programmers and broadcasters, both in the USA and in the UK, to discuss their perceptions of the cloud and its role in their strategic growth initiatives. While there is clear recognition of the value and power that cloud-based solutions bring to a media company’s fingertips, there also remains some hesitation in wholehearted adoption of the cloud that stems from historical perceptions – relating to concerns which we feel are being quickly resolved as technology and commercial offerings evolve.

These findings are published in our new white paper, “Empowering Multiscreen Workflows through the Cloud“, which debunks four key pitfalls media companies often fall into when considering the cloud for deploying online video offerings. The paper also discusses our suggested best practices for success in a cloud-based video ecosystem. It does so in the context of real world case studies derived from our research. Further, we examine concrete business benefits that cutting edge cloud-based solutions such as Aventus from iStreamPlanet can bring to a modern media business aspiring to succeed in the new online world order. Aventus powered NBC’s recent online video offerings for the Sochi Winter Olympics in a definitive showcase of the production-grade capabilities of today’s cloud based media workflow solutions. A copy of the white paper can be downloaded from www.istreamplanet.com/nab-2014/frost/.

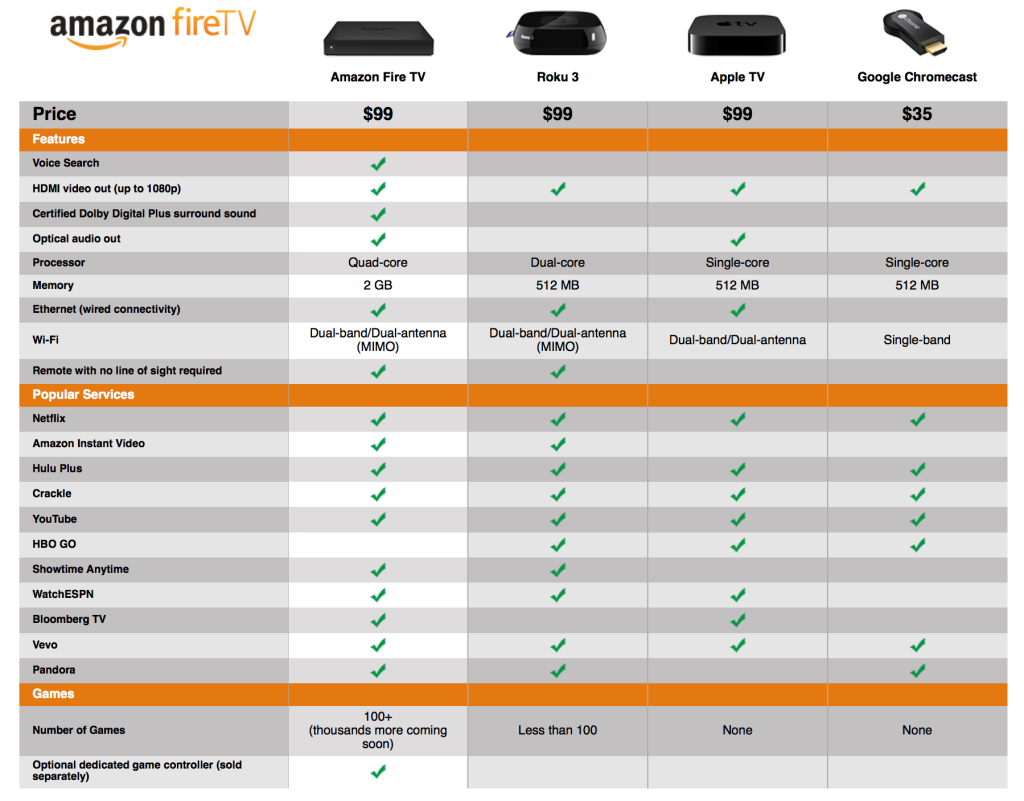

We’re expecting to see continued innovation in bringing cloud-based workflows to market. Online video is going to continue to grow, as are annual shipments of connected video devices. New devices and services that aim to make it easier for consumers to find and consume online content will continue to emerge at rapid pace – such as Amazon’s recent Fire TV announcement. The cloud will accordingly become more and more critical to helping media companies realize the monetary potential of this ecosystem while remaining competitive and differentiated in a fiercely fought market.