New Study From M-Lab Sheds Light On Widespread Harm Caused By Netflix Routing Decisions

On Tuesday, M-Lab released a new study on the impact of network interconnection on consumer Internet performance. The report entitled “ISP Interconnection and its Impact on Consumer Internet Performance“, details findings based on the speed test results collected by its test servers for various ISPs throughout the country over a roughly two-year period. For those not familiar with M-Lab, they provide the largest collection of open Internet performance data used by the FCC, amongst others, for the Measuring Broadband America program.

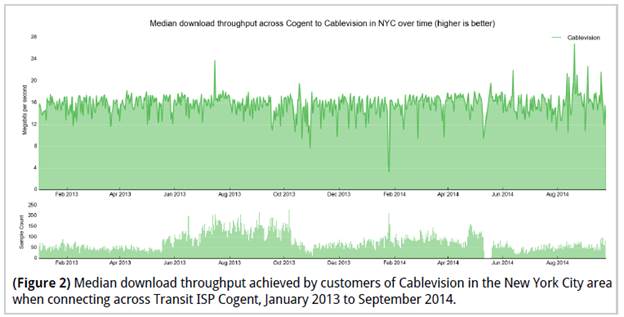

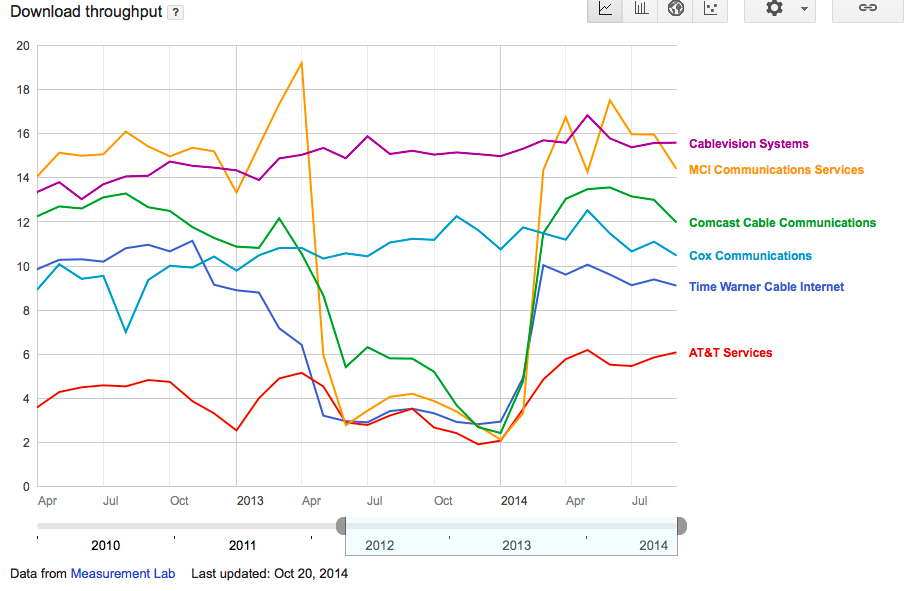

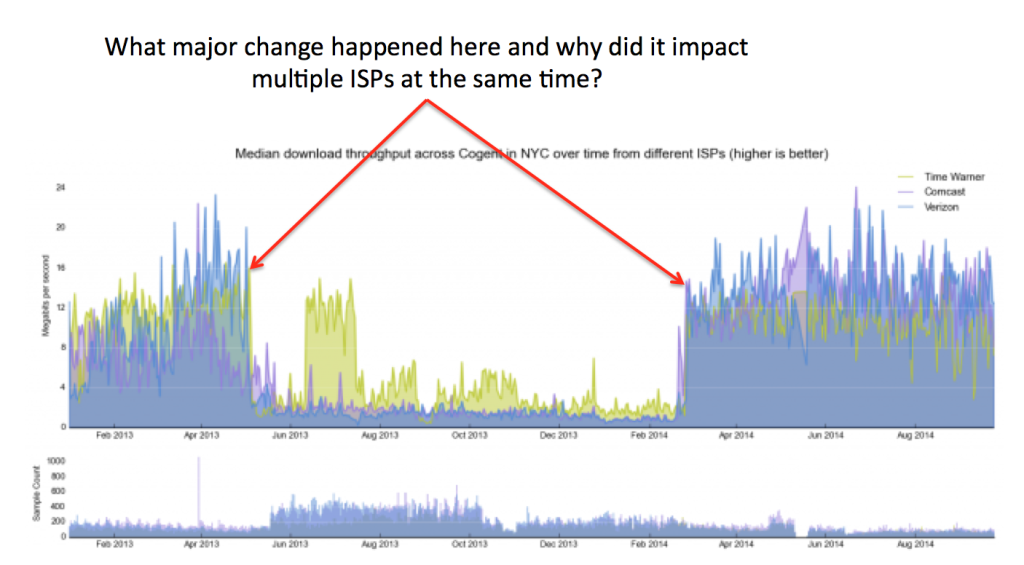

M-Lab data shows that around May 2013, suddenly and simultaneously throughout the country, speed test results for many ISPs (AT&T, Comcast, CenturyLink, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon) experienced a sudden and significant decline in performance to a specific set of transit providers (Cogent, Level 3 and XO). Just as suddenly around March 2014 the performance returns to normal for most of these same ISPs. Coincidentally, a few other ISPs who Netflix had negotiated direct Open Connect connections (Cablevision and Cox) did not experience similar decline in performance. The data presented in the study confirms what myself and others have surmised about Netflix being ultimately responsible for the dramatic, simultaneous decline in Netflix performance for all non-Open Connect ISPs.

If you look at the M-Lab measured history of the congestion, you will notice that these timelines line up very closely with Netflix’s migration from 3rd party CDNs onto their own Open Connect platform. The performance impact also matches closely with ISPs that did not agree to provide Netflix with Free Peering while other ISPs that agreed did not experience a performance impact.

Looking at Figure 1 from the report (below), we can see that performance suddenly degrades for three of the four major broadband companies in the NY metro area according to an M-Lab test server housed on Cogent’s network in NYC around May 2013 and then performance suddenly improves for all three around March 2014. This tight coordination of impact for multiple ISPs simultaneously suggests that the cause was not something done by the ISPs, but rather by another entity. (Note: I added the heading and arrows to the chart)

Looking at Figure 1 from the report (below), we can see that performance suddenly degrades for three of the four major broadband companies in the NY metro area according to an M-Lab test server housed on Cogent’s network in NYC around May 2013 and then performance suddenly improves for all three around March 2014. This tight coordination of impact for multiple ISPs simultaneously suggests that the cause was not something done by the ISPs, but rather by another entity. (Note: I added the heading and arrows to the chart)

What entity might be responsible? Well, figure 2 shows us that the fourth broadband ISP in the NY metro area testing on the M-Lab server on Cogent’s network, Cablevision (the only one of the four with a direct connection to Netflix’s Open Connect CDN) did not experience the same sudden drop/rise in performance over their link to Cogent.

What entity might be responsible? Well, figure 2 shows us that the fourth broadband ISP in the NY metro area testing on the M-Lab server on Cogent’s network, Cablevision (the only one of the four with a direct connection to Netflix’s Open Connect CDN) did not experience the same sudden drop/rise in performance over their link to Cogent.

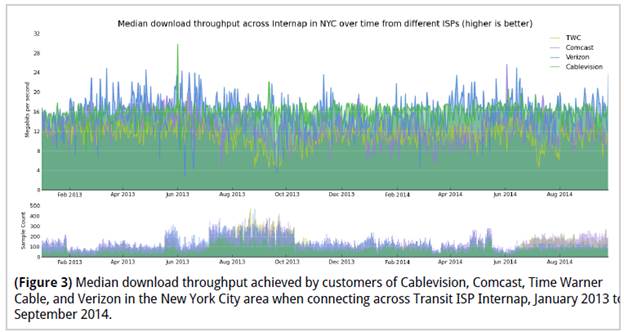

Finally, M-Lab’s report also helpfully includes performance results for all four broadband ISPs in NY from a test server located on a different backbone connection (one that was not providing transit service to Netflix) showing no sudden performance changes for any ISP.

The report also shows that direct interconnection agreements between Comcast/Netflix increased performance for other ISPs. Unless there were performance issues further upstream of the interconnection, there should have been no impact on the interconnection agreement between Comcast/Netflix on other ISP networks. And according to M-Lab’s findings, performance issues on ISPs networks were not due to technical issues but rather the business deals between ISPs. They say, “we were able to conclude that in many cases degradation was not the result of major infrastructure failures at any specific point in a network, but rather connected with the business relationships between ISPs“.

While some may want to take this report as a smoking gun that ISPs are causing congestion, they may forget, not understand, or purposely leave out, the fact that large content providers control the delivery of their traffic and can AVOID congestion. A recent MIT study “Measuring Internet congestion: A preliminary report” pointed out the fact that the ISPs singled out in this report have multiple alternative paths to reach them. The report states that, “Congestion at interconnection points does not appear to be widespread. Apart from specific issues such as Netflix traffic, our measurements reveal only occasional points of congestion where ISPs interconnect. We typically see two or three links congested for a given ISP, perhaps for one or two hours a day, which is not surprising in even a well-engineered network, since traffic growth continues in general, and new capacity must be added from time to time as paths become overloaded.”

Most agree that when Netflix, again, moved their traffic off of these newly congested paths to direct connections, performance improved both for Netflix services as well as other services impacted by this new congestion. What is puzzling however is the timing of this improvement. If you look at the graph above you will notice that all ISPs improved simultaneously in Feb 2014. This is the exact same time that Netflix and Comcast migrated traffic to their direct connection. While it is understandable that Comcast would improve, no one has explained how a Comcast direct connection would improve AT&T, Verizon, and Time Warner unless there were additional problems between the Netflix server and their transit ISPs themselves. When Netflix moved this traffic their congestion within their transit ISPs improved other destinations.

What M-Labs is trying to do is good for the Internet, but they need to expose more of the end-to-end problem. If they truly want to understand Internet congestion and user experience, they need to not only focus on interconnect, but they also should expand their measurement to the quality of transit ISPs and acknowledge the choices content sources make when delivering traffic to their customers. For example, a measurement can identify if there are material differences between a variety of OTT sources such as Amazon Prime, Netflix, Hulu and YouTube on a given ISP. If Amazon Prime HD video quality was excellent, but another source was poor, it would be interesting to determine why that’s occurring, and what options the content provider has to improve their services.

While many were quick to blame ISPs for problems consumers were having with their Netflix streaming experience, we’ve now have a lot of data in the market showing that the choices Netflix made directly impacted the quality of their video and other services as well. Between this new M-Lab data, the interconnection findings published by David Clark at MIT/CAIDA, this data, and a recently published research report that says Netflix is using calls for greater net neutrality to drive down the prices they pay, it’s now clear just how much control Netflix really has over the quality of video they deliver.